For more than 60 million years, penguins—like the adventurous Magellanic penguin—have been driven by an evolutionary instinct to push beyond familiar borders. Today, they’re showing up in some of the most unexpected places.

When Pablo “Popi” Borboroglu first set foot on a remote stretch of Patagonia’s eastern coastline back in 2008, he wasn’t sure what he’d find. The National Geographic Explorer was answering a call from a local rancher who had spotted a few penguins wandering his property. What Borboroglu discovered, though, was far from a pristine paradise: trash, broken glass, abandoned vehicles, and scorched campfires littered the area. “The place was a disaster,” he remembers. “It was full of garbage.”

But hidden among the debris, under bushes and tucked into small burrows, was something extraordinary: 12 Magellanic penguins, about a foot and a half tall, each marked by a white band wrapping around their eyes and neck. Normally, these penguins breed on rocky, sandy shores around South America before migrating north toward Brazil and Peru each winter. The nearest known colony was over 80 miles away—yet here they were, settling and breeding in a seemingly hostile environment.

Borboroglu quickly got to work. He freed a penguin caught in plastic and began the slow, careful job of cleaning up the site. Against the odds, the fledgling colony survived, raised chicks, and returned the following spring. Scientists have different theories on why some penguin groups, called “founder groups,” venture so far from established colonies. For Borboroglu—who later founded the Global Penguin Society, a major international conservation organization—this new colony was a shining example of penguins’ resilience and adaptability. “They’re so brave and determined,” he says. “They’re amazing.”

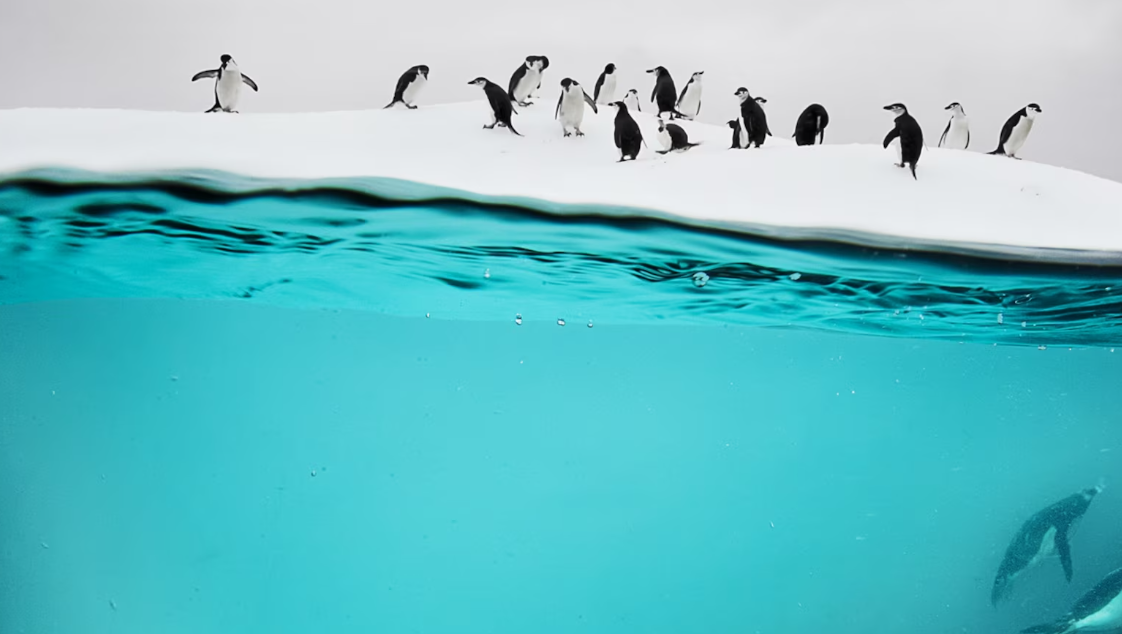

Penguins certainly capture the imagination. Their amusing waddle, dapper black-and-white appearance, and tender parenting behaviors have made them symbols of conservation. But these traits also reveal their incredible ability to adapt to the harshest environments. Penguins first evolved around 60 million years ago in what is now New Zealand. Some scientists suggest that the lack of land predators helped penguins shift away from flight, becoming instead masters of the ocean. Over time, they developed thick layers of fat, dense waterproof feathers for insulation, streamlined flippers for swimming at high speed, and that distinctive tuxedo-like pattern to confuse predators underwater.

Early penguins traveled far, riding ocean currents to new habitats. Emperor and Adélie penguins adapted to the brutal cold of Antarctica, growing thick fat layers, scale-like feathers, and clawed feet to grip the ice. Galápagos penguins, on the other hand, evolved smaller bodies and thinner plumage to survive near the Equator. Magellanic penguins historically lived on offshore islands, but after sheep ranchers eliminated predators like pumas and foxes, they established colonies on the mainland too. “Penguins vote with their feet,” says National Geographic Explorer Dee Boersma, a leading penguin biologist at the University of Washington. “They go where the food is.”

Yet no matter how far they roam, modern penguins are facing many of the same threats. Around half of all penguin species are now considered threatened with extinction. Last year, the African penguin was classified as critically endangered. In the ocean, penguins face oil spills, algal blooms, entanglement in fishing nets, and plastic pollution, while overfishing and warming seas diminish their food supply. On land, they’re up against shrinking Antarctic sea ice, coastal development, and predators—both old and new.

Over the past century, as penguin numbers dwindled, conservation efforts stepped up. Nations banned egg harvesting and created protected areas, offering some populations a fighting chance. Conservationists like Borboroglu and Boersma have since pushed for even stronger protections, including regulating shipping routes to help prevent oil spills near breeding sites.

One troubling discovery is that penguins now have the slowest evolutionary rate of any bird species, making it harder for them to keep up with rapid environmental changes. Yet many still manage to adapt. Emperor penguins, for example, relocate their colonies when sea ice melts in one area. Satellite imagery has even revealed new emperor colonies in Antarctica. King penguins, relatives of the emperors, are declining in some areas but making a comeback in others after being heavily hunted in the past. Gentoo penguins, meanwhile, are expanding southward as warming seas open up new breeding grounds. “We’re seeing new colonies established further and further south,” says Gemma Clucas of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Back in Patagonia, the handful of Magellanic penguins that once huddled among garbage have sparked something remarkable. As Borboroglu partnered with landowners and officials to create a 35,000-acre wildlife refuge, more penguins arrived every year. Today, over 8,000 Magellanic penguins nest there. “Its growth has been remarkable,” Borboroglu says. “It shows that nature can thrive if we give it a chance.”